CARRIE – 2001

*

I am just about to go home to my shoddy hotel when I run into him.

There, alone on the Plaza de Mayo, standing below sickly-looking trees with the rose-tinted presidential building hovering behind him. Is he some kind of guard?

No, his uniform looks old and worn. Is it a sailor’s? He hands out some kind of leaflet.

I walk closer.

He sees me. “Would the señorita care for something to read?”

I see the lines on his face clearly, like a map of some scarred coast. I don’t want him to be more than 40 but he looks older. Hair slightly greasy and he has stubs.

Okay, so he is not in service. Not in anybody’s service anymore, it would seem.

I take the leaflet. It is poorly printed, written by a typewriter. There’s a lot in Spanish that I can’t digest with only a few seconds of skimming, but it’s something about a pension for retired military servicemen.

“That’s right … ” His voice is whispering and coarse at the same time. “They deny us our rightful pension. After all we’ve done. Makes one think, right?”

I nod politely. “That … is unfair.”

I close the leaflet. On its back is a photocopied cut-out of a map. Now those shapes I recognize. “The Falklands … ”

Something twinkles in the depths of his dark eyes. “You know Las Malvinas?”

“Sorry, Las Malvinas. Yes. My father went there.”

“He did? Which unit?”

“I don’t remember. I was very little. I’m … sorry. For the war and everything … ”

He shakes his head. “It had nothing to do with you. And your father had to do his duty. So did I.”

“I guess so.”

I feel pushed to go on, like the couple of tourists who passes us, heading for the presidential palace. Somewhere deep in my gut, I know I should not stay.

I look away. “You must think I’m just a stupid turista.”

A thin smile crosses his lips. “You look like a turista, but not stupid.”

I nod, and I hope he doesn’t notice that I don’t feel like looking directly into his deep black eyes.

Suddenly it’s like I can’t breathe.

Oh no … not now.

“Senorita?”

“It’s nothing. I have to hurry.”

It’s here and I can’t fight it.

I hate it. But it’s here.

I turn abruptly and head back for the little hotel in that narrow alley a stone’s throw from the central station.

I’m not sure if he watches me, as I go. I want him to, but I am ashamed, so if he doesn’t it would be better.

*

The next day the sun is out, which is another surprise. The mist is still lurking somewhere out at sea. The streets are less crowded but the ever-present droning of traffic from a million cars you can’t even see reminds you that this is Buenos Aires—a capital.

My veteran is standing like a silent sentinel exactly where he stood yesterday, handing out leaflets, which most people reject.

I walk over. “Hola …”

“Ah, the beautiful señorita is back. What a pleasant surprise.”

“People don’t often come back?”

“Nobody ever comes back.”

I avoid his eyes and try to find somewhere around us to focus. A few people have found their way to Plaza de Mayo, along with me, but not many. A lone Japanese tourist, lost in his love affair with the camera; an old man picking up garbage and putting it into a can; a smart lady talking into a cell phone, adjusting her sunglasses. They all seem strangely upbeat even though you can’t see it directly if you look at them. They don’t smile, but they seem to be filled with some kind of … energy.

Something I longed to have myself.

A sense of somewhere to go?

The man smiles vaguely. He still wears the faded uniform, as if he hadn’t changed from yesterday. “So I take it you are here to face the enemy, señorita?”

“We are not enemies”

“That’s not what I meant. I was just—” He suddenly lapses into a cough.

I instinctively take a step forward, but then stop myself before I go too far. “Are you all right?”

He nods, then with a gesture he bids me sit down on the hard stone of a small ‘wall’ they built to protect some of the fresher-looking flower beds dotting the plaza in front of Casa Rosada.

The sun is up, but it’s still damp and cold.

“Never mind,” he says. “It doesn’t matter. Perhaps nothing does. I should know, after trying to make people read for years.” He waves a handful of leaflets then drops them back into his bag.

“I read it.”

He frowns. “Oh … I hadn’t expected that.”

“What did you think? That I would throw it away?”

“Most people do.”

“I don’t.”

“If you read my leaflet—” he muses “—then you must either be more accomplished in Spanish than pretty much every other blonde gringa coming here, or more patient, or both.”

“Or I could just be someone who doesn’t know what to do with my time.”

He pauses, looks out over the Plaza, regarding for a while the multitude of people coming and going, to and fro. Like he was used to it. Then the question comes, as sudden and sharp as if he had drawn a knife. “Why did you come back?”

“I … read your leaflet.”

He grins coarsely. Then he extends his lab. “Miguel Sanchez Palomino—encantada, señorita.”

A gust of wind from the South Atlantic passes between us.

I take his hand. “Carrie Sawyer.”

“‘Soier’?”

“Close enough.”

“North American?”

“Close enough.”

“You are a strange gringa, Carrie Soier. Not like I would have imagined.”

“I am not like I would have imagined.”

The coarse laughter again, brief and hard. Then he is silent for a while, like he suddenly revealed an opening and he wants me to forget about it.

Another horde of tourists passes by, led by a small red-haired girl who frantically tries to be heard in three different languages.

“You’re not going to give them some leaflets?” I ask.

But he just shakes his head, looks down. “They will not read it. And even if they did, it would make no difference. They don’t live here and they will quickly be gone again.”

“Does it make a difference that I read it then?”

“Maybe.”

“Is there anyone else who could read it and then it would make a greater difference?”

“Perhaps …” It is as if he is looking at someone far away now.

“I mean, I would like to help—”

He looks at me again, hostility in the blackness of his eyes. “‘Help?’… Have you come to mock me?”

“No. Of course not!”

He shakes his head and gets up.

I reach out, without thinking, and only just manage to catch his sleeve. I realize I look rather pathetic. “Miguel, I’d like to buy you a coffee—or a beer—if you want it.”

“Now you are mocking me.”

I get up, ready to give him hell. Who does he think he is? But I get a hold of myself. “I’m serious.”

He snorts. “And I don’t want to.”

“I’m not trying to—”

“I know what you are not trying to—that was never on my mind, señorita. But that which you are trying to do is perhaps even more loathsome to me. Go away.”

He walks away. Briskly.

Damn. I …

He forgot his bag.

I look again.

Yup.

I grab the green army bag … and run a few steps.

But he’s gone.

*

I don’t know what to do, except spend some more time drifting around downtown Buenos Aires. I take the bag with me, although I probably shouldn’t.

By day, B.A. is a friendlier big city than you’d expect, even with the loud boulevards, the plethora of multi-storied buildings stretching for the sky, and the incessant sidewalk chatter in Italianized Spanish from passers-by.

But as the sun sets, I become more and more focused on the labyrinth of shadows between the buildings. Despite the sounds of laughter from the throng of sidewalk cafes, I have this vertiginous feeling that I have to keep moving in order not to be trapped in one of them.

So I seek shelter in one of the Italian restaurants. The service is friendly. Not many customers this hour. An air condition propeller turns lazily in a corner. What I needed.

Outside the window, there’s roaring Avenida Corrientes, but now that I’m inside it’s like it’s sufficiently muted; enough for me to sit here in a half-lit corner and get my thoughts together.

I order mineral water and study the menu engagingly, although I’m really not hungry.

I sit in that hideaway spot all evening until other people begin to show up for supper at around 9 PM. I manage to make a little bit of pasta and two slices of bread last 4 hours. I have also ordered a single glass of white wine but I don’t drink it all. I like to drink, but not alone. Not yet in any case.

I think a lot about if I should finally get in touch with all those people I haven’t talked to in months: my mom, my brother, Julia—perhaps even … no. Not him.

What should I say anyway? Have I really found anything during these—what, a million months or so ago—that was worth leaving for?

Isn’t the truth really that I have only bad reasons left?

But like a good little addict I keep sucking on them—‘the reasons’—my imaginary lozenges of explanation—hoping they’ll yield a bit more of that sugar that kept me going thus far: the equally imaginary promise of salvation.

It’s like, when I said goodbye to Nadine back in Columbus—in my previous life, before my sojourn to this ‘exotic continent’; she was one of many friends that could’ve been a lasting one. But she never really got to be any more than a study mate. I don’t know if I decided that it was going to be like that or it just happened. But I didn’t make an effort to get closer, although I sure as hell needed a friend after …

Or how about that spunky Canadian backpacker I met at Lake Titicaca? We hit it off immediately. So naturally I had to leave the next day before we hit things too well. I was afraid of ‘too well’.

Or Julia back in Chapare. That was special. And I stayed, finally, with her. Until I left. Only with imaginary explanations. God, she must be angry.

*

The night has caught up with the city but I still sit here. I refuse more service for the third time and the waiter glares.

I just look at the bag.

I haven’t opened it.

I won’t.

I pay up and leave.

*

The cold South Atlantic waters can no longer be stopped from pressing through your nose, mouth, into your lungs;—the inevitability of the breathing reflex is remarkable, even when there’s nothing to breathe but heavy sub-Arctic seawater …

I am torn out of sleep when I can’t breathe.

Wait … I … can breathe. I’m … alive. Here. In the Hotel Perón with the peeling wallpaper.

Near the Retiro. I can hear the brakes of the trains.

It’s deep night. The city is not asleep. I don’t think I’ll be sleeping either.

I’ll be thinking about why I am going back to look for Miguel tomorrow, and why it is so important that I have not looked in the bag.

His bag. It’s there. On the floor, beside my too-short bed with the cement mattress.

What do I want?

*

Breakfast the next day consists of a pitch black coffee, as usual. Then I ditch the hotel and head for the subway.

Line B from Retiro Station to Leandro N. Alem, switch to Line C, and voila—Plaza de Mayo 15 minutes later. I only rode it twice until now, but it feels like I’ve done it a million times before.

Something tugs in me, something I should consider. But I shove it away.

The plaza is almost deserted. They must still be holding a siesta or something. A few seagulls drift lazily above, looking down on us indifferently as if they’d say, ‘We’ve seen it all before’ … ‘We’ve seen it all before’.

But he is here, like a mirror of yesterday, standing in the shadow of the Pirámide de Mayo, handing out his poorly photocopied leaflets.

I walk over. Not too fast. Not too slow.

Miguel sees me but doesn’t even nod.

I breathe deeply. “I’m sorry for what I said yesterday. I was being stupid.”

A little twitch appears around the mouth, but he says nothing.

“I brought … your bag.” I put it down on the ground. “I have not looked in it.”

Something … changes in his face, like a little part of the invisible shadow on it fades away. He shakes his head a bit, then watches the seagulls. Then his gaze falls to the leaflets. There’s a huge stack in a cardboard box. Same size as before—the stack. Then he looks directly at me.

He takes a step forward—suddenly, he snatches the bag.

“Thank … you.” But his gaze is still filled with suspicion.

“You … really have not looked? In it?” He looks as if he’d believe any answer I’m ready to give.

I shake my head.

“Why?” he inquires sharply.

“For the same reason, I came back. I want to—” Now it’s my turn to shake my head “—I don’t know. But I know that I didn’t want to make you angry yesterday. I just wanted to … a cup of coffee … you know … ”

He nods. “You really didn’t look in my bag?”

“I didn’t.”

“You are strange.”

“I just respect people’s privacy.”

“Do you want to know what was in the bag?”

“Not if you don’t want to tell me.”

“There was a manuscript of a book I’m working on.”

“Oh …”

“I taught history in school, before the Malvinas War. When I came home I wanted to write about immigrants to our country. A kind of family history. But … I couldn’t. So I started writing about this war. I made it into a kind of novel, but it’s based on the truth.”

The bag didn’t feel that heavy. In fact, it didn’t feel like there was much in it at all. I wonder how big his “manuscript” is, but I don’t ask.

“Well, about that cup of coffee … if you don’t want to, I understand.”

His eyes narrow again, but he treats me to another smile. Like a soldier smiling before he shoots, perhaps? “A cup of coffee would be nice, señorita Soier. But not like this.”

He takes off his worn uniform blouse and pulls a t-shirt from the bag I just brought him. I take a quick glance but I don’t see much else.

He leads me over the plaza to an indistinct bar on the other side of Avenida Hipólito Yrigoyen. It is half-empty at this time.

An hour passes. Then two. We chat about everything and nothing. I notice that even though he looks ruffled his hands are clean and he smells of soap and deodorant.

He talks about his family, and it’s unclear if they are still in touch. Sometimes he talks as if they are. Sometimes not.

I tell him about Ohio, Scotland, all sorts of superficial things about my life. And then … Lin.

He nods gravely. “I know what it’s like to lose.” Then he orders more coffee and insists on paying.

It’s strange because I am not ashamed but the moment before I told him it struck me that now I would feel relief. And it just came … And I feel nothing.

But then he says, “So in March, just before we sailed for the Malvinas my little sister asked when I would come home, and I said, ‘When the war is over’, and she asked, ‘How long will that be?’ Can you believe her? ‘Stupid cow’, I said, ‘that is why you don’t make women soldiers when they ask such questions. Of course, she ran away to her room, crying.”

He pauses, holding his half-empty cup out in front of him like that skull from Hamlet, and bites his lip. “Maybe … I shouldn’t have said that.”

I cross my arms, wanting to come up with some acknowledgment of his shame but not without subtle reproach. But the emptiness in his eyes makes me reconsider “Do you regret it?”

“Every day. Oh, she says she has forgotten. But we are not really on speaking terms these days.”

“Because of what happened then?”

“She was just a little girl. So no. I think it’s something else. Life … ”

“A lot of time has passed.”

“Yes.”

I try to find some opening, to tell him more about myself. But it feels like I’m searching for a crack in a wall that I can’t find. And he seems like he is lost in his own thoughts, anyway.

“Anyway,” he says “when I got back from the war, she was away at a boarding school and … many things had changed.”

“Changed how?”

He puts the cup down with an audible clang. The elderly waitress bats an eyelash as she passes us but says nothing. I say nothing, too.

His somber eyes lock with mine. “Why are you here?”

I want to make a snap reply now. I have thought about this for several days, believe me. I have thought about how not to make him think …

… Suddenly I hear the screams of drowning men.

No. We are alone. We are just us. We are in a cafe. A bar. A something. A normal … place. And outside is the street, its sounds muted, like …

Like, I’m underwater…

He grabs me before I hit the ground. Strong grip, it feels almost effortless. All I am aware of. The rest is … spinning.

Miguel and the waitress get me away from the bar and those high chairs and over to a regular table, and down on the sofa behind it.

“I’m … all right.”

“No, you are not.” Miguel plumps down beside me, no real effort to respect my space.

Maybe the time for that has passed.

The waitress’ eyes flicker. “Voy a llamar a un doctor.”

Miguel waves her away. “Give us some water, please.”

I don’t remember much else, except … insisting that I must go home alone. And that it takes a while for him to relent. But he does.

*

The next day he is not at the Plaza. And I feel bereaved.

But why?

He is a stranger.

I should be moving on. I should be going to Torres del Paine. Or Bariloche. Maybe Brazil. I don’t know …

But I’m stuck in the prison of a city of millions.

*

Another day passes and another.

I don’t have that much money left but I talk to Mr. Lynch, the hotel owner, into letting me stay in a smaller room for half the price.

I decide enough is enough, and one morning I check on the Plaza one last time, and … there he is.

I can’t help smiling. Maybe it’s because he actually looks like something is shining in him when he sees me.

Good poker face, but I know what I saw.

“Hola, Miguel!”

He nods. “Señorita. I hope you are feeling better. I also hoped you had left the city.”

I was about to shake his hand. “Uh … no, I haven’t left.”

The shining fades. “Perhaps you should have. There are so many wonderful places to see in Argentina, and a poor old sailor like me is not worth your time.”

“Of course, you are. I like talking to you.”

He holds his breath and I can see he is searching for something again. Looking for something. Not between us but … out there.

There is the presidential palace, the May Pyramid, the flowers. But it’s none of those things.

“Here.” He holds out one of his Falklands War leaflets.

I regard the leaflet skeptically. “I already … have one of those.” He keeps nudging it towards me—as if he’d want to stick it on my t-shirt or something.

“No, no—” he says impatiently. “I want you to write to me where you stay—your hotel. If you want … ” He hesitates.

I take the leaflet hesitantly. “Do you want to—”

He holds up a hand as if to silence any further discussion. “I will pick you up. At 8. I want to show you my city. You deserve it. Not like this. Like … we are real people.”

“Okay … do you, er, have a pen?”

Wait—what am I doing?

“A pen?” He slips a hand into the breast pocket of the venerable uniform. It comes up empty. “I must have forgotten it.”

I try to laugh a little. “No pen? You have to have one if you want my hotel. And what about your mission? You have to hope that people have their own pens with them—so they can sign your petition!”

He shakes his head again, but for the first time, a smile seems to be creeping up on his lips. Like it had been lying in ambush all the time. “You’ll just have to tell me. I’ll remember.”

“The Peron, near the old railway station. You know it?”

“I do. Who doesn’t know Peron?”

For a moment, it’s like I’m not here. I’m watching myself talking to him. I’m turning around, asking someone else questions about what this derelict young turista is doing.

I get no answers.

So I provide my own. “That’s good, then. You can pick me up at 8.”

He nods. “Good.”

A voice screams from somewhere far away in my head: What the hell are you doing? Does he think I’m crazy? Or just pathetic?

Or is he so desperate that he thinks I’m so desperate and this is the clownish movements before a little roll in the hay or some sweat-stained bed in a clammy motel? He must be at least 45—God …

Miguel looks like he is about to swallow some of that humid air that seems to be lying heavy over the main plaza this afternoon. “I don’t know … what to say.”

“You’re not supposed to say anything.” I shrug. “You just invited me out. That’s all.”

“This is a stupid idea,” he then exclaims. “Stupid, stupid … ”

“If you’re not going to come, that’s okay, but I’ll be waiting at 8. I trust you. Ask for Carrie ‘So-ieer’ in the reception.”

“You really want me to show you the city, señorita? What kind of woman are you?”

Now I feel I have him where I want him. I’m not sure where that is, only that it’s there. That I am where I need to be now. “I am apparently not the woman you thought I was. But if you think about me that way again, I might not come down when you stand there at 8.”

“I thought you would say no. You don’t know me.”

“I know you somewhat by now. Isn’t that enough?”

“Maybe.”

I watch him again, not wearily anymore, kind of attentively. He’s got a sea of lines under his eyes, making him look even older, but that’s not important.

“As long as it’s just to show me the city,” I say, with new confidence.

“Of course, it is,” replies. “I feel I … owe you.”

“You don’t owe me anything.”

“But I do.”

“Okay … ”

“Your Spanish is excellent, by the way”—he gets back to the topic with a suppressed hint of admiration—“if you are this good at speaking our language it should mean you are patient. Not like—” He gestures angrily at a random couple passing by. I have no idea if they are tourists or not, like me, but they look very much in love.

“Well, patient people are seldom loco – crazy,” he then adds and smiles quickly. “That is enough for me.”

“I’m not that patient. But I’ve been traveling for a long time. And about the only thing I was good at in school was languages. Do you still want to show me around tonight?”

He looks directly at me. “Do you still want me to?”

“ … Yes.”

“Good.” He nods more slowly, then takes a deep breath. “I will see you, then. 8 o’clock. Peron.”

“8 o’clock. Peron.”

I nod a final greeting and slowly begin to walk as if I have something else to do on the Plaza. Slowly. I don’t want to break the moment. It is a contradiction.

Perhaps if I stay he’ll regret it. Or I will. Maybe we’ll regret it all later. We still have time for that—and to screw up. Two total strangers, so totally incompatible, don’t just do things like this. Do they?

Perhaps you’re just only good at making weird friends, Carrie Sawyer, so you might as well accept it. You are weird yourself, not like everybody else—who’s weird in their own right. You’re weird-weird. You’re someone who’s on the fringe. Not normal. You might as well act the part. Embrace it.

Hell, yeah …

I look back over my shoulder, carefully.

He is not looking back, but I get the sense again that I am on his mind, as he sits by the flower bed, with his stack of folders, hands in his lap, and contemplates the uncaring passers-by. Representatives of the world …

I turn, look back at him. “Miguel—why do you say that patient people are seldom loco?”

He regards me with an inscrutable expression. “Well, patient people are able to wait until the madness has left them. That’s really all there is to it. And madness comes to all of us, if we live long enough—it comes in some form or other.”

“That sounds very philosophical.”

“It is not. I was a history teacher, remember? Before I went to war. There is a close relation between history and philosophy.”

I nod and walk away, without saying goodbye, without shaking hands.

He is not gonna show up.

*

Night envelops Buenos Aires again. And with it I am enveloped in more strange dreams about ice-cold seawater pushing into my mouth. It’s like Miguel’s bag is still in my room. I know what is in it, and yet I did not look in it.

Or … have I not been sleeping at all, since I came home, just imagining things? Some days it is hard to tell.

Outside my hotel a hooker howls in frustration over a customer that apparently drove away without paying for a job in the car just below the dead lamppost at the corner; there is the even more distant howling of horns from taxi cabs squeezing each other to get the last customers in front of the Retiro station; transistor radios blast through wide open windows in the apartments opposite our building and in our building—bad pop music from the more seedy discos in the barrio of Barracas where I’m staying.

Funny, because in the day, Buenos Aires seems relatively mild, despite its subdued Latin American passion and the occasional soccer brawl; it’s mild in attitude, even welcoming in places—unlike, for example, L.A., which I’ve been to a few times. Sucked big time. Didn’t like it. Maybe if you lived in Beverly Hills, but then you’d just be a bird in a gilded cage, wouldn’t you?

Maybe Ohio wasn’t so bad. Or even Skye …

Careful, Carrie—don’t get over-sentimental. Just find that single clean black blouse you have, the least-worn-looking pair of jeans and that comb you use too seldom. And then Mr. Miguel Sanchez Palomino won’t get any ideas of the sort of men who are 20 years older than you might easily get. I’m not gonna look the part.

It could still go horribly wrong, though … What was I thinking?

Probably wasn’t …

Look, girl—he is not dangerous.

I don’t sense any danger.

He.Is.Not.

And God knows, if it comes to that I’ve already had some experience … in Bolivia, for example. Because I’m not very good with men …. and … Jeesh, there’s a revelation!

But I believe that he is not dangerous in that sort of way. If he says he’s okay with doing something impulsive because he knows (and we both admitted to it—sort of)—that otherwise, he’s just gonna be standing there the next morning, equally alone, with equal pointlessness … Well, then he is okay with it. Then he has a reason that’s as good as mine.

That’s always the bottom line for me, isn’t it? I am weird and therefore good at meeting weird people in weird ways. So far it hasn’t got me killed. Or raped. Or both.

*

… Phone in my room is ringing. I almost tear it off the wall.

Not because I’m eager but because it is very poorly fastened to the wall. After some initial swearing, I get the message. The receptionist, good ol’ Mr. Lynch, is trying to tell me the impossible.

He is here. He actually came.

Ohgodohgod—so now what do I do? Go down? Stay …

Why the … ?! Now hear this, Carrie—you get in that blouse and you go down, and if you have any doubts then just go home—all the way to Ohio and become a washing lady or something. After everything you’ve been through. Where’re your guts?! Christ, for a gonzo-leap into the land of self-discovery, for someone who tries to be impulsive you are—

Okay.

Enough. Enough already.

I’ll go down. Easy now. Just sleep on the blouse. Check my wallet, credit card, keys.

That’s it.

I’m ready.

I’m ready.

…

I really am.

I open the door as if I’m sleepwalking. Then I go down.

*

Place: The pitiful excuse for a lobby in Hotel Peron

Miguel is waiting. And he looks every bit like … I didn’t expect.

White shirt, ironed—half open at the top. Shaven. Hair actually bears marks of contact with comb. He looks … strange.

Like I only saw him as a soldier—I mean, sailor. No. Really, it was worse—as a vagabond. Before. How is that possible? How can I have marked him up like that in my mind?

I know, goddammit, that people are people, more than just what the hell they wear or where they go or the jobs they take or the leaflets they hand out … I know that … !

This is so scary, that for a moment it makes me hesitate on the stairs. He misunderstands.

“Señorita Soier … ” he slowly manages to say, in lieu of a more formal greeting, and all the time while swallowing … something—“I’d like to take you out. If you still want to.”

I swallow, too, feel my own breathing … as if I have to force it, along my steps. Then I walk all the way down. Extend my hand …

“Hola Miguel … I’m ready. ¿Vamos?”

Mr. Lynch behind the reception desk, venerable, mountainous in his calm, smiles broadly—like our age difference didn’t matter. Maybe it doesn’t. Or maybe it’s just a relic from an old age where men were always allowed to go out with younger women without being frowned upon, an Age that kept existing in Argentina and a few other places but died a long time ago in the rest of the ‘modern’ world.

I take his arm, put it into mine.

“What are you waiting for?” I whisper. “Let’s go. Don’t want Señor Lynch to think something about us, do we?”

“No—of course not.”

We head out the revolving doors, into the warm night.

I said he was not going to come. In a way I was right. He came but that part of him that would’ve taken the lead did not come, perhaps it never could. Maybe it drowned a long time ago, somewhere off the Falklands?

What is it I want to know?

*

I should’ve quit at the first danger sign—that is when he insisted on us driving in his own car and not taking a taxi. I should have just gone away then. But after all that struggling with myself to prove that I was not afraid and didn’t care if … Well, I didn’t.

The real shit started, though, when he suddenly turned off the expressway, down a minor road without lighting that ended in a container lot of some sort. We had been talking fairly normally, albeit awkwardly, up till then—actually, we had been talking quite well from the moment we left Hotel Peron.

Miguel had first asked if I wanted to come with him to someplace called “Tigre” where his brother owned an “acclaimed” restaurant. I said yes, because what else should I say? I had gone this far with him. Why question the fact that a guy like Miguel really might have a brother with a restaurant that got stars in the local newspapers?

Then we reached his car, an old Sedan that looked like it was only running on goodwill. I hesitated. I discovered that I was still in the process of making my real decision. The problem was that I didn’t even know for sure why I had done this. I only knew I didn’t want to date him for real—you know, go home with him and all that—or anything.

Of course not! But this was kind of like a date, wasn’t it? The problem is always like that: If you have never made up your mind entirely if you don’t know your own reasons, someone else will tell you what they are.

He puts his hand on the handle of the car door. “Shall we?”

I step into the car.

Half an hour later, on the expressway going north—moments before he turns. I have to ask about it.

“Why do you write about your experiences in the Falklands War in a novel? You said you did write a novel.”

He glances at me. Streaming shadows seem to run between all the little furrows in his face, like small dark snakes. “Do you really want to know?”

“ … If you want to tell me.”

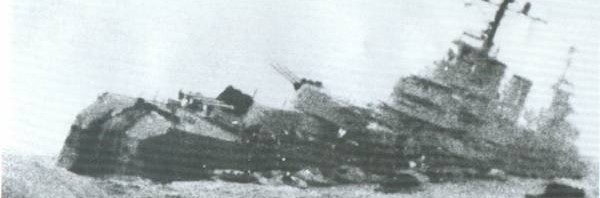

He gazes out into the dark before us. “I write a historical novel because I can not—ever—write down my own memories about the war. I can not. I can only write it from a distance, through someone else. There’s … a shadow inside my mind. It seems to descend whenever I try to think about what happened that day—2 May 1982. You see, I was a sailor on the Belgrano … ”

“The warship that was sunk … !”

“By a British submarine, yes.” He nods grimly. “I was on it. So were Fher and Nestor—two of my best friends. They didn’t make it. I remember trying to keep Fher up in the water but … he slipped away from me. He reached for me, called my name he … Anyway, I was in the water for a long time before I was picked up. It felt like a tomb … but that is life—”

He punches it; sharp, aggressive over-taking of a huge truck; doesn’t even wait to see if there’s opposing traffic. Something in my stomach lurches.

“—it always ends sooner than we would like and we have no control about when, where, how—no control whatsoever. We believe we live under an open sky but in reality, we live in a tomb just waiting to be closed.”

He speeds more. The old Sedan lurches forward. I’m pressed back into my seat.

“Miguel, please—don’t—”

He ignores me. Totally.

“So—” he says with uncanny calm as he accelerates ever faster “- I’ve got to write about it through somebody else—it is the only way to get it … out. Hence, I chose a ship from another war, another sailor—a ship that was also sunk, like the Belgrano I was on. It’s a great idea. There’s only one problem … ”

I can’t breathe again. “What is the problem?”

He looks at me again and the snakes are still there. “You need to be a patient man to start writing a book. And I am not a patient man.”

I look at him and I know only horror. “You never had a script in that bag—!”

And that’s when he suddenly brakes hard, and hurls the car off the expressway, away toward the end of the world.

*

He brakes again to make the car stop between two gigantic, steel-gray containers. Two seconds before, I try to tear open the door and jump out, but he grabs my arm and then hits me, fist right in the face—almost knocks me cold. Then he drags me out onto something that feels like wet concrete smelling of urine and rainwater.

“You thought you were clever, puta!” he spits as he spins me around, pushes me forward, hammers my head into the hood. I see black spots and white pain. He tears away my blouse, bra. Jeans take a few moments longer, but they come down.

“You … thought … I was some kind of animal in a zoo, that you could pity! You thought that, huh?”

“No … I … ”

“Callate, puta! Shut up!”

Then comes the pain. And now I struggle—wildly. At one point I manage to tear myself loose, twist myself around, and hit him in the face. I claw at his shirt collar, ripping it. He hits me again. Then he flings me around again, hammers my head once more into the hood and I almost go out.

“Puta!” he screams again. “You lie! You did think I was someone you could pity. You little gringa whore … coming down to Buenos Aires for a trip to the veteran zoo… wanted to go out and then just leave me somewhere—but with something to tell all your little girlfriends back home—puta!“

*

For those of you who haven’t tried to be raped .. I can tell you that it’s nothing like those porn fantasies you sometimes read on the net. Or have yourself.

You don’t just panic. You become panic. It’s not that it hurts, or that his cock may stink of piss or that maybe he has a disease or anything like that.

It’s because your body is being invaded—YOU are being invaded. And that feeling is the most terrifying of all.

“Miguel—no! Please … !!”

“Shut up! Shut UP! Aaah—aah—aaaah … ”

It begins, and my mind begins to shut down … like I’m sinking into myself, sensing the old darkness from … a time long ago, opening itself up inside my heart again and trying to swallow me from the inside out. I don’t want to live through this. I just want … to run away.

Suddenly …. a small metallic clink … beside my bloodied, battered face. A necklace—his necklace … it’s got a small medallion in it … it dropped onto the hood. Must’ve been loosened when I tore his collar …

It’s a medallion of the Virgin Mary.

For some reason, though, I reach for it, clench it in my hand—hold on to it while he finishes. I don’t know if it’s that or if my body’s instincts somehow take over and inject my brain with some of that morphine-like endorphin-whatever that you sometimes hear about people getting doped by when in acute danger … but somehow I relax more after I hold the medallion. The panic seems to recede … now there’s just a haze.

When Miguel comes inside me, he howls, like a wounded animal. The howl is guttural, dirty, crazed—and it echoes between the silent container blocks. Then he collapses on top of me; I hear the creaking of metal from the hood as both our weights press it down.

I lie very still for many minutes and so does he. I clutch the little hard oval-shaped medallion in my hand, feeling every millimeter of the fragile delicate chains that keep the necklace together. Then I feel him drawing away, finally.

I just lie there, sperm and blood all over my buttocks, clothes torn, feeling the chill of the night wind over my skin—as a skeletal hand.

I slowly turn around, still clutching … it.

I look at Miguel. He sways. He looks oddly sad, there in the dark, trying to pull up his trousers.

“My medallion,” he then blurts, staring fixedly at my hand. I open my hand. We both see it … her. Now … he … doesn’t take it back. I stretch out my hand toward him.

“No … ” It’s almost a whisper on his lips. “Keep it.”

“It’s yours,” I say, feeling still in a daze like nothing else matters. The surreality of it all. It doesn’t matter. Just give the damn thing to him before he decides to hit me again. Or worse.

But Miguel shakes his head vigorously.

“No, I won’t have it.”

He turns, begins to back away, into the darkness.

“Who gave it to you?” I call after him, not really knowing what made me.

He stops.

“Who gave it to you?” I ask again, still wondering. Maybe I still want to know … something?

“Mi madre … ” I then hear him whisper with his back to me. He turns again, towards me.

“My mother gave it to me. I… had forgotten it.”

I get on my feet, suddenly feeling something … I haven’t felt for a long time. In a moment, I’m going to hate him.

But not now …

I put the torn necklace in his hand, close his hand around it with both my hands. I don’t look him in the eye.

It’s like there’s just a big, white silence inside me.

Then I pull my trousers all the way up and begin to walk back towards the freeway.

Towards the surface.

*

I don’t go to the police. I think about it of course, but I don’t go. To the pharmacy, sure. But no police.

Mr. Lynch back at the hotel doesn’t ask questions and I have no idea why. I look like hell. He just gets a maid to come up and help me wash and bandage and ask if there is anything more I need and when I say ‘no’, she doesn’t come back. But there is something I need, so I go out again to a 24-hour store.

In the morning then I haven’t slept at all and I’m all drugged up on caffeine and cheap booze. It’s a wonder I can still walk down the stairs to the ancient computer that Mr. Lynch has lovingly installed on a small table across the minuscule reception desk.

‘Free for use for guests’—whenever it works that is…

I sit for a long time, staring at the screen.

I turn on the patched-up stool, it is swaying but holding.

Mr. Lynch is sleeping behind his counter, it seems.

“Señor Lynch?”

His eyes are suddenly open. Was he watching me after all?

“Señorita?”

“I know this is a strange question—but you wouldn’t happen to know anyone who lives on The Falklands—Las Malvinas?”

Mr. Lynch frowns, then he smiles, but not as broadly as usual. “Why?”

“I’m interested in the War … ”

“It is not a topic for a young lady like you.”

“But my father was there.”

“So was my brother. He is home now. Is your father home?”

“Yes, but–”

“Then think no more of it,” Mr. Lynch says “The War is past. You have all of your future to think about.”

Mr. Lynch then shuts his eyes again, leaning heavily back in his armchair. I turn back to my screen. After a few more moments, and some breaths that seem to last forever, I pull close the keyboard and begin to rewrite my own ending:

<Hey there, long time … >

*

Last edited 2 Aug 2023